Failure Theories - A361

| Failure Theories | |

|---|---|

| Foundational knowledge article | |

| |

| Document Type | Article |

| Document Identifier | 361 |

| Themes | |

| Tags | |

| Prerequisites | |

Introduction[edit | edit source]

This page introduces and discusses various failure theories that have been developed to analyze and predict when a composite material is expected to fail.

Fundamentals[edit | edit source]

A number of different failure theories exist for composite materials. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and the selection of an appropriate failure criterion for an application is the responsibility of the designer and/or the design authority. Most people are familiar with the von Mises failure theory, which applies to metals, however, because composite materials fail in different ways, such as delamination, and have more complex stress states, due to their fiber-reinforced structure and anisotropic mechanical behaviour, the same measure is not used for composites. Simpler failure theories, such as the Maximum Stress or Strain criteria, are straight-forward and failure indices can easily be calculated by hand. However, the Maximum Stress or Strain failure theory only considers stress in one direction at a time, and does not account for the interactions between stresses. More involved theories such as Tsai-Wu and Hoffman account for stresses in the longitudinal, transverse and shear directions.

Application[edit | edit source]

One way to define failure is to determine when the first ply in a laminate would fail and reduce the total load capacity of the part. The failure theories introduced in this sections provide a method for calculating the failure index of a given ply. This method is called First Ply Failure (FPF) and determines the minimum stress for failure in each ply. With FPF, the laminate is assumed to have failed when the first ply fails. One of the advantages of first ply failure is that it is numerically straight forward and easy to use. When the failure index, \(FI\), is below 1, the ply has not failed. When the failure index is equal to 1, failure is imminent. When the failure index is above 1, the ply has failed. The use of first ply failure is both conservative from a safety perspective and computationally less intensive than progressive ply failure. A ply is considered to have failed when the failure index (\(FI\)) is above 1 for that particular ply [1].

If the response of the system beyond first ply failure is required, progressive ply failure should be used. In this method, the analysis will continue after the first ply failure with decreasing stiffness of the system as the failure propagates through additional plies.

\(FI < 1\) – No failure

\(FI = 1\) – Failure imminent

\(FI > 1\) – Ply has failed

| Variables used in the following sections are summarized below | |

|---|---|

| \(\sigma_x\), \(\sigma_y\), \(\sigma_z\) or \(\sigma_1\), \(\sigma_2\), \(\tau_{12}\) | Applied stresses |

| \(\varepsilon_x\), \(\varepsilon_y\), \(\varepsilon_z\) | Applied axial strains |

| \(\gamma_{xy}\), \(\gamma_{xz}\), \(\gamma_{yz}\) | Applied shear strains |

| \(X\), \(Y\), \(Z\) | Ply axial strengths (subscripts \(T\) or \(C\) for tensile, compressive) |

| \(E_x\), \(E_y\), \(E_z\) | Ply axial Young’s moduli |

| \(S\), \(R\), \(T\) | Ply shear strengths in xy (in-plane), xz, and yz directions (respectively) |

| \(G_{xy}\), \(G_{xz}\), \(G_{yz}\) | Ply shear moduli |

Maximum Stress, Maximum Strain[edit | edit source]

Maximum Stress and Maximum Strain do not consider the interaction between different types of stresses (i.e. longitudinal, transverse, and shear). However, they are commonly used in evaluating the strength of adhesively bonded joints [2]. Additionally, consideration can be given to using the maximum strain theory for predicting failure in the resin rich layer of a part.

\[\frac{\sigma_x}{X}<1, \frac{\sigma_y}{Y}<1, \frac{\sigma_z}{Z}<1\]

\[\varepsilon_x < \frac{X}{E_x}, \varepsilon_y < \frac{Y}{E_y}, \varepsilon_z < \frac{Z}{E_z}\]

\[\gamma_{xy} < \frac{S}{G_{xy}}, \gamma_{xz} < \frac{R}{G_{xz}}, \gamma_{yz} < \frac{T}{G_{yz}}\]

Tsai-Wu (Tensor Polynomial - Strain Energy)[edit | edit source]

Tsai-Wu, also called the Tensor Polynomial Theory, is a quadratic equation that considers the interaction between different types of stresses simultaneously, including both the tensile and compressive stresses. It requires an experimentally derived interaction coefficient, \(F_{12}\).

\[F_1 \sigma_1+F_{11} \sigma_1^2+F_2 \sigma_2+F_{22} \sigma_2^2+2F_{12} \sigma_1\sigma_2+F_{66}\tau_{12}^2<1\]

where

\[F_1 = \frac{1}{X_T}-\frac{1}{X_C}\] \[F_{11} = \frac{1}{X_TX_C}\] \[F_2 = \frac{1}{Y_T}-\frac{1}{Y_C}\] \[F_{22} = \frac{1}{Y_TY_C}\] \[F_{66} = \frac{1}{S^2}\]

The term \(F_{12}\) must be evaluated experimentally and is constrained by a stability criterion as follows:

\[F_{11}F_{22} - F_{12}^2 > 0\]

Due to practical difficulties in experimentally obtaining this interaction coefficient, it has been suggested that for highly orthotropic materials, \(F_{12}\) may be set to zero [3].

Hoffman[edit | edit source]

The Hoffman failure criterion is a quadratic equation that takes into account the interaction of shear stresses and both tensile and compressive stresses in the longitudinal and transverse directions. It is similar to Tsai-Wu, but makes an explicit assumption regarding the interaction coefficient, F12. The equation is given below.

\[\frac{\sigma_{1}^2}{X_T X_C}-\frac{\sigma_1 \sigma_2}{X_T X_C}+\frac{\sigma_2^2}{Y_T Y_C}-\frac{(X_T-X_C)}{X_C X_T} \sigma_{1}-\frac{(Y_T-Y_C)}{Y_C Y_T}\sigma_2+(\frac{\tau_{12}}{S})^2 < 1\]

Tsai-Hill (Maximum Work)[edit | edit source]

The Tsai-Hill failure theory is a quadratic equation that considers the interaction between different types of stresses, but assumes the same strength allowable in tension and compression (i.e. \(\sigma_1 = \sigma_t = \sigma_c\)).

\[(\frac{\sigma_1}{X})^2-(\frac{\sigma_1 \sigma_2}{X^2})+(\frac{\sigma_2}{Y})^2+(\frac{\tau_{12}}{S})^2<1\]

where

\(X = X_T\) if \(\sigma_1 > 0\)

\(X = X_C\) if \(\sigma_1 < 0\)

\(Y = Y_T\) if \(\sigma_2 > 0\)

\(Y = Y_C\) if \(\sigma_2 < 0\)

Failure Envelopes[edit | edit source]

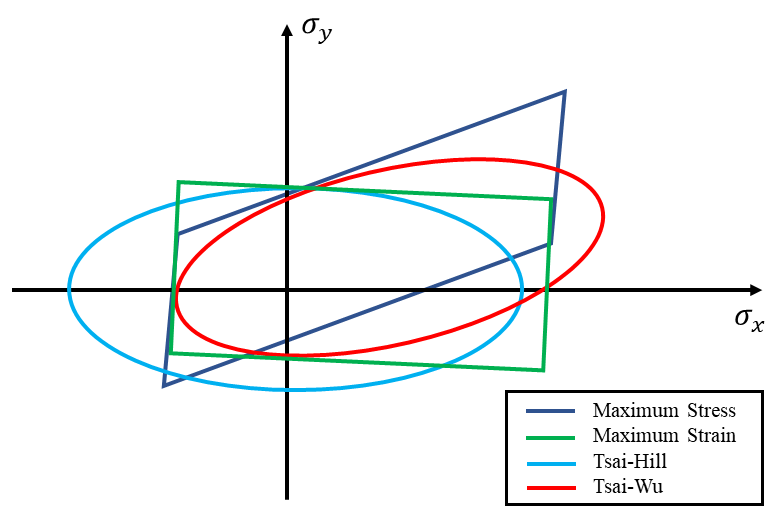

A failure envelope is a plot (typically in 3 dimensions) of the combinations of the normal and shear stresses that can be applied to a material to cause failure. Typically, drawing 3D plots is cumbersome so a common approach is to plot contours of constant shear stress on a \(\sigma_x\) vs \(\sigma_y\) plot. If an applied stress is within a given failure envelope, the lamina will not fail.

With a maximum stress criteria, the shape of failure surface is a simple orthogonal failure surface when plotted in terms of stress components. Similar to the maximum stress criterion but based on strain values instead of stress, the failure surface in maximum strain criteria is typically represented as an orthogonal box when plotted in stress space. The Tsai-Hill failure surface is elliptical (or ellipsoid in 3D stress space). This criterion accounts for stress interactions by considering the combined effects of normal and shear stresses in the material's failure, which leads to a more complex failure surface. The Tsai-Wu failure surface is generally ellipsoidal in 3D stress space and more complicated than the Tsai-Hill surface. It accounts for more material parameters (including interaction terms between normal and shear stresses) and has a higher degree of interaction between stresses. As can be observed in the figure below, different failure theories will produce different results, which emphasizes the importance of selecting an appropriate theory for a given application.

Case Study[edit | edit source]

As an example of a CAD/CAM software for composite design and manufacturing, Siemens NX offers nine possible failure theories to select for a given analysis. Care must be taken when selecting a failure theory to ensure that it is appropriate for the chosen materials.

- Von Mises Yield and Von Mises Ultimate are only applicable for plies that have isotropic material properties.

- Puck only applies to unidirectional plies. It requires four empirical parameters that must be found experimentally, although the NX Help menu gives typical properties for glass/epoxy and carbon/epoxy.

- LaRCO2 is only applicable for unidirectional plies.

- Maximum Stress and Maximum Strain do not consider the interaction between different types of stress (i.e. Longitudinal, transverse, and shear).

- Hill is a quadratic equation that considers the interaction between different types of stresses. It compares the applied stress to tensile and compressive strength allowables, but does not consider tensile and compressive allowables simultaneously.

- Tsai-Wu is a quadratic equation that considers the interaction between different types of stresses, as well as both the tensile and compressive strength allowables simultaneously. It requires an experimentally derived interaction coefficient. The NX help menu recommends an assumed value that can be used for the interaction coefficient if experimental data is not available.

- Hoffman is very similar to Tsai-Wu but makes an explicit assumption regarding the interaction coefficient.

In this work, Hoffman failure criteria is used since it considers the interaction of longitudinal, transverse, and shear stresses. The equation also accounts for both tensile and compressive strength allowables. The advantage of Hoffman over Tsai-Wu is that it does not require the specification of an experimentally derived interaction coefficient. When using Tsai-Wu failure theory, care must be taken to ensure that each ply material has an interaction coefficient defined. If an interaction coefficient is not entered, the solver assumes the value to be zero and results in a large margin of error.

Consideration can be given to using the maximum strain theory for predicting failure in the resin rich layer of the composite plate. Strain values at which the plate will begin to crack can be recorded from tests and be fed to the maximum strain criteria to predict if cracking will occur for a given load case.

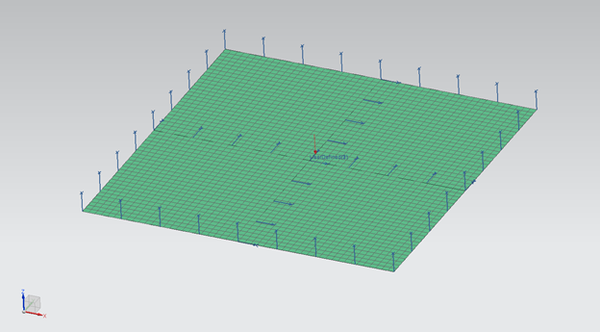

The following example is used to illustrate the differences between the various failure criteria. Consider a square plate that is 200 mm x 200 mm. The plate is made from eight plies of E-LTM 1808 with a laminate schedule of [0/90/0/90]s. The plate is simply supported along all four of its outer edges and a 2000 N bending load is applied in the centre of the plate. The analysis setup is shown in the next figure.

The allowable strengths for E-LTM 1808 is shown in the table below while the other table gives the stress in each of the directions for the top and bottom plies. It should be noted that the stresses in Ply 1 are tensile, while the stresses in Ply 8 are compressive. These values were used to calculate the strength ratio using Maximum Stress, Hill, Hoffman, and Tsai-Wu criteria.

For all four failure theories it can be observed that the strength ratio increased for Ply 8 due to the higher compression strength allowables. The strength ratios for Ply 1 are all clustered close together. However, we start to see some large differences for Ply 8 due to the compressive nature of the applied stresses. In particular the Hill criteria predicts a much larger strength ratio because the interaction term is assumed to be the tensile strength allowable if the longitudinal and transverse stress have the same sign (positive or negative). This helps to illustrate the danger of using the Hill criteria if compressive forces are likely to occur.

| Strength Allowables for E-LTM 1808 | |

|---|---|

| Longitudinal Tensile Strength (MPa) | 276 |

| Transverse Tensile Strength (MPa) | 317 |

| Longitudinal Compressive Strength (MPa) | 317 |

| Transverse Compressive Strength (MPa) | 421 |

| Shear Strength (MPa) | 103 |

| Stress at Top and Bottom Plies due to Bending Load | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ply 1 | Ply 8 | |

| Longitudinal Stress (MPa) | 133.1 | -133.1 |

| Transverse Stress (MPa) | 132.9 | -132.9 |

| Shear Stress (MPa) | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Strength Ratio Results due to Bending Load | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ply 1 | Ply 8 | |

| Maximum Stress | 2.07 | 2.38 |

| Hill | 2.37 | 4.69 |

| Hoffman | 2.18 | 3.41 |

| Tsai-Wu | 1.97 | 2.93 |

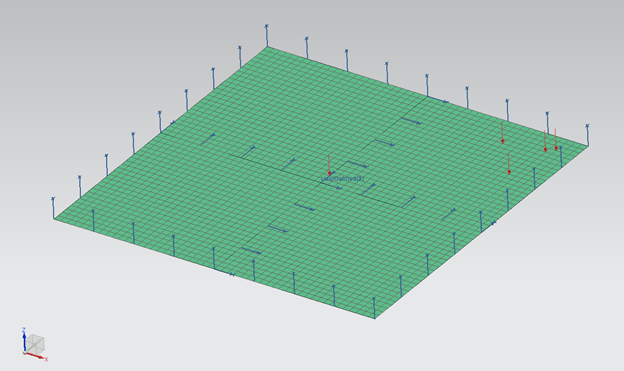

The same analysis setup was employed, but additional forces were applied near the corner to induce nearby shear stresses. The analysis setup is shown in the Figure 3. The following tables provides the stresses in Ply 1 for this particular setup and the strength ratios. We can see that the shear stress is now a significant component of the total stress. The strength ratio for the maximum stress criteria is now based on the shear stress, but does not take into consideration the longitudinal or transverse stresses. This causes the strength ratio value for the maximum stress criteria to be higher than for the other failure theories. This is because the other failure theories all consider the interaction effects between the longitudinal, transverse, and shear components.

| Stress at Top and Bottom Plies due to Bending and Shear Loads | |

|---|---|

| Ply 1 | |

| Longitudinal Stress (MPa) | 44.4 |

| Transverse Stress (MPa) | 43.7 |

| Shear Stress (MPa) | 29.1 |

| Strength Ratio Results due to Bending and Shear Loads | |

|---|---|

| Ply 1 | |

| Maximum Stress | 3.55 |

| Hill | 3.18 |

| Hoffman | 2.98 |

| Tsai-Wu | 2.92 |

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

A selection of failure theories for composites has been presented in this article, each with associated advantages and disadvantages. The selection of an appropriate failure criterion is the responsibility of the design authority, and the theories discussed here should not be considered an exhaustive list. For additional information on these and other theories, the included references provide further detail.

References

- ↑ [Ref] Hopkins, Peter.; National Agency for Finite Element Methods & Standards (Great Britain) (2005). "Benchmarks for membrane and bending analysis of laminated shells". NAFEMS. ISBN 1874376085. Retrieved 3 July 2024. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ [Ref] Heslehurst, Rikard Benton (2013). Design and analysis of structural joints with composite materials. DEStech Publications, Inc. ISBN 1605950343.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ [Ref] Narayanaswami, R; Adelman, Howard M (1977). "Evaluation of the tensor polynomial and Hoffman strength theories for composite materials". 11 (4). Sage Publications Sage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA. ISSN 0021-9983. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

| About | Help |

Welcome

Welcome to the CKN Knowledge in Practice Centre (KPC). The KPC is a resource for learning and applying scientific knowledge to the practice of composites manufacturing. As you navigate around the KPC, refer back to the information on this right-hand pane as a resource for understanding the intricacies of composites processing and why the KPC is laid out in the way that it is. The following video explains the KPC approach:

Understanding Composites Processing

The Knowledge in Practice Centre (KPC) is centered around a structured method of thinking about composite material manufacturing. From the top down, the heirarchy consists of:

- The factory

- Factory cells and/or the factory layout

- Process steps (embodied in the factory process flow) consisting of:

The way that the material, shape, tooling & consumables and equipment (abbreviated as MSTE) interact with each other during a process step is critical to the outcome of the manufacturing step, and ultimately critical to the quality of the finished part. The interactions between MSTE during a process step can be numerous and complex, but the Knowledge in Practice Centre aims to make you aware of these interactions, understand how one parameter affects another, and understand how to analyze the problem using a systems based approach. Using this approach, the factory can then be developed with a complete understanding and control of all interactions.

Interrelationship of Function, Shape, Material & Process

Design for manufacturing is critical to ensuring the producibility of a part. Trouble arises when it is considered too late or not at all in the design process. Conversely, process design (controlling the interactions between shape, material, tooling & consumables and equipment to achieve a desired outcome) must always consider the shape and material of the part. Ashby has developed and popularized the approach linking design (function) to the choice of material and shape, which influence the process selected and vice versa, as shown below:

Within the Knowledge in Practice Centre the same methodology is applied but the process is more fully defined by also explicitly calling out the equipment and tooling & consumables. Note that in common usage, a process which consists of many steps can be arbitrarily defined by just one step, e.g. "spray-up". Though convenient, this can be misleading.

Workflows

The KPC's Practice and Case Study volumes consist of three types of workflows:

- Development - Analyzing the interactions between MSTE in the process steps to make decisions on processing parameters and understanding how the process steps and factory cells fit within the factory.

- Troubleshooting - Guiding you to possible causes of processing issues affecting either cost, rate or quality and directing you to the most appropriate development workflow to improve the process

- Optimization - An expansion on the development workflows where a larger number of options are considered to achieve the best mixture of cost, rate & quality for your application.

To use this website, you must agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.

By clicking "I Accept" below, you confirm that you have read, understood, and accepted our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.